Inside the Core this Week: Galileo, Darwin, and Genesis

Thursday, February 27, 2020

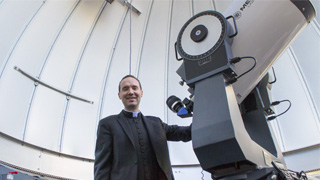

Fr. Joseph Laracy now teaches in the Core Curriculum.

In our class we viewed two film clips to explore the concept of creation in connection with faith and science. The first of these, Bishop Robert Barron's discussion of "Creation" addresses the meaning underlying the Genesis accounts. Unlike other early myths of creation, most of which involved violence and overthrowing of one god or gods by another god or group, the Genesis story shows a non-violent creation story, featuring a God who delights in his creation, seeking and nurturing a personal relationship with humans, and who clearly loves the natural world, including humans, that he has brought into existence. Later we will read from Pope Francis' Laudato Si, which uses the best of scientific theory about the environment to underline how human beings should interact with the natural world in an ethical way. When this encyclical was first promulgated in 2015, some criticized the Holy Father for delving into a topic supposedly reserved for science, but, like John Paul II, Francis argues for the two perspectives of faith and science to support each other, particularly in this time of climate crisis. He says, "If we are truly concerned to develop an ecology capable of remedying the damage we have done, no branch of the sciences and no form of wisdom can be left out, and that includes religion and the language particular to it" (63), as quoted by Rev. Nicanor Austriaco in Bioglogos, June 23, 2015.

The second clip is from the film Theory of Everything about scientist Stephen Hawking. The early part of the film shows Hawking and his future wife meeting and falling in love. Both graduate students at Cambridge, the couple might be said to epitomize the perspectives of purely scientific rationalism on the one hand (Hawking) and literary, humanistic faith (Jane, his future wife) on the other. She is pursuing a Ph.D. in medieval Iberian poetry, and he is a physicist and cosmologist. Very early in their relationship they disclose to each other his atheism and her Anglican Christian faith. Despite their differences, they are intensely drawn to each other. At a university dance, the two go outside and look at a night sky brilliant with stars. Hawking is clearly moved, as is Jane, who begins to quote from Gen. 1 – "In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth…." They look at each other, and he takes her hand; then they begin to dance, then kiss. The scene evokes a symbolic depiction of the dance that can be had between science and religion, if the two approach each other with appreciation and respect, even delight in their differing but compatible perspectives. In all of its complexity, the Catholic intellectual tradition includes both science rooted in reason and poetry rooted in faith, and can celebrate the beauty of their inter-connectedness.

Categories: Education, Science and Technology