Historian and Philosopher Will Durant

Friday, July 27, 2018

William Durant

Will Durant was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and a Pulitzer Prize; he was both a faculty member and a student at Seton Hall.

The author of 53 books during his lifetime, Durant is best known for The Story of Philosophy and the 11 volume set, The Story of Civilization, which he produced with his wife, Ariel.

Written in a manner designed to make the subject matter accessible to everyday people or "the common man," the books were extremely popular. His first, The Story of Philosophy, sold 3,000,000 copies and made The New York Times best seller list.

Published between 1935 and 1975, The Story of Civilization "sought to unify and humanize the great body of historical knowledge."

It was also a best-seller. As noted by The New York Times in Durant's 1981 obituary: "Rousseau and Revolution, which won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction in 1968 and was a Book-of-the-Month Club choice, was a best-seller, as were the 10 other volumes. This meant total sales of more than two million copies in nine languages, a readership enjoyed by few historians."

William and Ariel Durant

H.L. Mencken described the volume on Caesar and Christ as the "best piece of historical synthesis ever done by an American."

The New York Herald Tribune, known as "a writer's newspaper" (it won at least nine Pulitzers in its 32 years of existence and employed John Steinbeck, Tom Wolfe, Red Smith and Jimmy Breslin to name but a few), said of Durant's work: "There are certain passages which may well bear comparison for sheer literary power with anything in contemporary literature."

In 1975 The New York Times stated that Will and Ariel Durant were "The greatest historians of our time."

In addition to the Pulitzer prize the Durants received in 1968, in 1977 they received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest award granted by the United States government to civilians.

The Story of Civilization was again reissued in 2009.

At Seton Hall

William Durant graduated from St. Peter's College in Jersey City and is said to have "devoured every book he could," becoming "a fixture at the Newark and Jersey City Public Libraries."

After St. Peter's, Durant took a job as a reporter with the New York Evening Journal. His parish priest and confidant, Monsignor James Mooney, had become rector of the seminary and President of Seton Hall. Soon thereafter, Durant came to live on campus, where he entered the seminary and taught Latin, French and geometry in the college while also serving as librarian – a position he relished given his unfettered, everyday access to "the stacks" and the pageant of great minds contained within their pages.

Faith vs. Intellect

Although later in life he seems to have reconciled the two, at Seton Hall Durant grappled with what he perceived to be the conflicts of faith and secular intellectualism; he ultimately came to see the decline of a civilization as the culmination of that strife writ large. He later wrote:

Hence a certain tension between religion and society marks the higher stages of every civilization. Religion begins by offering magical aid to harassed and bewildered men; it culminates by giving to a people that unity of morals and belief which seems so favorable to statesmanship and art; it ends by fighting suicidally in the lost cause of the past. For as knowledge grows or alters continually, it clashes with mythology and theology, which change with geological leisureliness. Priestly control of arts and letters is then felt as a galling shackle or hateful barrier, and intellectual history takes on the character of a "conflict between science and religion." Institutions which were at first in the hands of the clergy, like law and punishment, education and morals, marriage and divorce, tend to escape from ecclesiastical control, and become secular, perhaps profane. The intellectual classes abandon the ancient theology and—after some hesitation—the moral code allied with it; literature and philosophy become anticlerical. The movement of liberation rises to an exuberant worship of reason, and falls to a paralyzing disillusionment with every dogma and every idea. Conduct, deprived of its religious supports, deteriorates into epicurean chaos; and life itself, shorn of consoling faith, becomes a burden alike to conscious poverty and to weary wealth. In the end a society and its religion tend to fall together, like body and soul, in a harmonious death. Meanwhile among the oppressed another myth arises, gives new form to human hope, new courage to human effort, and after centuries of chaos builds another civilization.

It can be said that that "certain tension between religion and society" existed within Durant. Although he later wrote that he considered Seton Hall "a paradise," his struggle with faith and his advocacy for socialism caused him to ultimately curtail his studies as a seminarian and to give up on his plan to synthesize the two creeds as a priest.

Durant later described his entry into the seminary as "an act of hypocrisy, generosity, idealism, and egotism. After two years I had had no success in recapturing either the old piety or the old faith. . . . The idealism and egotism were inextricably mixed, as they so often are. I took with Quixotic seriousness the mission I had assigned myself, of working within the Church to ally it with socialism."

'I Loved Seton Hall'; 'My Greatest Incentive to Live an Honorable Life'

When Durant decided to leave Seton Hall, University President Mooney treated him kindly, and Durant wrote: "as if to ease the transition for me and my parents he asked me to resume my former duties as a lay teacher in the college. I gladly agreed, for I loved Seton Hall." He continued to teach until the end of the semester. Durant was grateful to Mooney whom he considered to have been "my greatest incentive to live an honorable life."

Changing with Age

Although advocacy for socialism played a large part in his youth (and his departure from Seton Hall), as noted by University of Rochester history professor Joan Shelley Rubin, after World War I Durant began recognizing that a "lust for power" underlay all forms of political behavior.

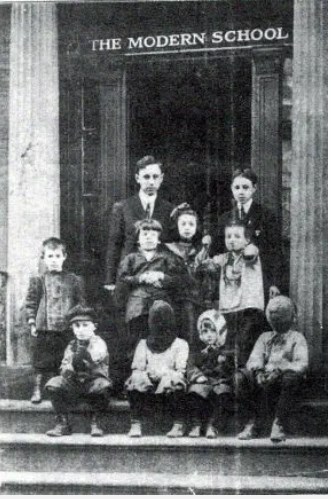

William Durant stands with his pupils outside the Modern School in New York City, circa 1911-12.

Durant visited the Soviet Union in 1933 and, much to the chagrin of the left, concluded in the Tragedy of Russia, that the country was ''a gigantic prison.''

As noted in an article on Durant in The National Review, former Saturday Review editor Norman Cousins said, "As a young man, he asked too many questions to be an authentic rebel, and in his later years he was too distrustful of the answers to be an authentic conservative."

Regardless of politics, at the end of that honorable life, Durant like Voltaire, returned to Catholicism and received the last rites.

For many years, however, there was a legend among the priests of the diocese that, after Durant left the seminary, Monsignor Mooney locked the Seton Hall library, and left it locked until he retired – lest any other seminarian read himself out of the faith.

More than 100 years later the University Libraries are decidedly open, with more than 1.5 million titles on hand— and proudly include The Story of Philosophy and multiple sets of The Story of Civilization.

It is a mistake to think that the past is dead. Nothing that has ever happened is quite without influence at this moment. The present is merely the past rolled up and concentrated in this second of time. You, too, are your past; often your face is your autobiography; you are what you are because of what you have been; because of your heredity stretching back into forgotten generations; because of every element of environment that has affected you, every man or woman that has met you, every book that you have read, every experience that you have had; all these are accumulated in your memory, your body, your character, your soul. So with a city, a country, and a race; it is its past, and cannot be understood without it.

Perhaps the cause of our contemporary pessimism is our tendency to view history as a turbulent stream of conflicts - between individuals in economic life, between groups in politics, between creeds in religion, between states in war. This is the more dramatic side of history; it captures the eye of the historian and the interest of the reader. But if we turn from that Mississippi of strife, hot with hate and dark with blood, to look upon the banks of the stream, we find quieter but more inspiring scenes: women rearing children, men building homes, peasants drawing food from the soil, artisans making the conveniences of life, statesmen sometimes organizing peace instead of war, teachers forming savages into citizens, musicians taming our hearts with harmony and rhythm, scientists patiently accumulating knowledge, philosophers groping for truth, saints suggesting the wisdom of love. History has been too often a picture of the bloody stream. The history of civilization is a record of what happened on the banks.

To read more about Will Durant and his time at Seton Hall as well as the "scandal" his lectures caused after he left to become principal of the Ferrer Modern School in New York, read "William Durant - Stealth Seminarian," published by the Immaculate Conception Seminary School of Theology.

Categories: Alumni, Arts and Culture, Faith and Service