Creator of 'We Can Do It!' Poster Uncovered

Thursday, April 21, 2022

Originally produced in 1943 by J. Howard Miller for the Westinghouse Corporation as part of the factory production effort during World War II, the "We Can Do It!" poster was mass reproduced in the 1980s and came to be a revered representation of female empowerment. Although iconic, the model for the poster as well as its creator were long shrouded in mystery and misinformation.

Over the last decade, Professor Kimble has painstakingly uncovered the truth behind the icon.

In 2018, his research on the identity of Rosie the Riveter went viral, appearing in People magazine, on the front page of the New York Times, on NPR and the television show Mysteries at the Museum as well other assorted media across the globe too numerous to list. The story achieved well over a billion media exposures worldwide.

Debunking the commonly held and much celebrated belief that a Michigan woman, Geraldine Hoff Doyle, was the model for the poster, Kimble unearthed the original photo that is believed to be the basis for the poster and, importantly, was the key to Doyle's claim as the poster's model.

The photograph Kimble discovered came complete with the original photographer's caption tag affixed to the back, which names Naomi Parker (-Fraley) in Alameda, California, as the subject of the photo – not Geraldine Hoff Doyle in Michigan.

Fortunately, Naomi Parker-Fraley lived long enough to see the historic record set straight and her identity as "Rosie the Riveter" celebrated throughout the world.

J. Howard Miller, Artist Who Created the ‘We Can Do It’ Poster

In his most recent research, Kimble set his sights on setting the record straight on the poster's creator, J. Howard Miller.

In "Famous but Unknown: An Introduction to J. Howard Miller," published by the University of Chicago's Source: Notes in the History of Art, Kimble notes:

The sparse information that has been published about Miller is tenuous at best. Some sources, for example, indicate that he was born in 1918 and died in 2004. Others only speculate, with "ca. 1915–1990" being a common guess. None of these dates are correct. Some sources indicate that he graduated from the Art Institute of Pittsburgh in 1939. He did attend that school, but many years earlier. Elsewhere, aside from reproductions of his most famous work, little but speculation about Miller's life has appeared in print.

Perhaps the most telling sign of Miller's enduring mystery is the confusion over his likeness. Although his life span was in living memory, he remains astonishingly faceless. Worse, most of the sources that do attempt to convey his likeness make a critical error. One recent exhibition at a reputable museum, for example, featured a creator's head shot next to a reproduction of the "We Can Do It!" poster. It was actually an image of a much younger man – who was not even a graphic artist.

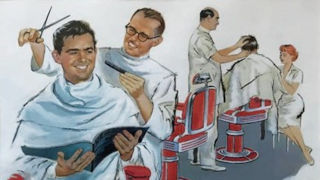

In his research on Miller, Professor Kimble draws "on obscure publications, archival sources, and interviews to present a brief introduction to the elusive artist behind the icon" and produces for the public the only known portrait of J. Howard Miller. In this portrait, an undated ad illustration, Miller inserted himself into the image as the self-assured, middle-aged barber in the foreground.

In this undated ad illustration, Miller inserted himself into the image as the self-assured, middle-aged barber in the foreground. Private collection.

"Unfortunately for J. Howard Miller – and the historical record – there was a photographer with the same name born about 20 years after the graphic artist," said Kimble. "The photographer's obituary along with an image is readily available online. Couple that with the fact that the resurgence of the Rosie poster as an iconic figure of women's empowerment did not occur until after the graphic artist's death, and we have what could be described as 'extremely fertile ground' for google-era misinformation. But hopefully, some old-fashioned research and this newly discovered portrait can set the record straight."

Facts and Observations, J. Howard Miller (1898 – 1985)

- James Howard Miller was born on October 27, 1898, in Wilmerding, Pennsylvania, only three miles from the site of the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company's massive new East Pittsburgh plant, where Miller would one day produce wartime morale posters.

- Miller studied at the Artists' League of Pittsburgh (later to become the Art Institute of Pittsburgh) as well as Carnegie Technical Institute (now Carnegie Mellon University) in its School of Applied Design. To make ends meet, he also worked part-time as a clerk at Wilmerding's Westinghouse Air Brake Company facility.

- By 1928, Miller was working full-time as a figure artist for Pitt Studios. He and his new wife, the former Mabel Adair McCauley, would eventually follow his developing career to stops in Cleveland and Detroit. His work in both places involved advertising art, but with a useful specialty: after his peer artists would finish depicting the actual consumer product for an ad, Miller would be called in to render an attractive model alongside the product to complete the visual appeal.

- With the onset of the Great Depression and the subsequent decline in advertising, however, Miller's career became more challenging. He took time away to study technique in Europe, frequently sketching passersby at outdoor cafes.

- By late 1942, the artist was working as a freelancer in association with Rayart Studios and Town Studios. Here his prior relationship with Westinghouse was helpful, as he was hired by Charles Ruch, the editor of Westinghouse Magazine, to create a series of in-house posters for the corporation's wartime labor-management committee. Miller would eventually create at least forty posters in the series, although only "We Can Do It!"—posted for two weeks within Westinghouse's various locations in February 1943 and then forgotten for decades—was destined for eventual fame.

- After the war, Miller's career in illustration art blossomed. As Ruch (the editor of Westinghouse Magazine) recalled, "he was, most likely, the best free-lance artist in Pittsburgh at the time." His precise gentlemen and sophisticated ladies graced pitches for Alcoa, US Steel, Duquesne Brewery, and many other local corporations and businesses. In this period, he inserted himself into an ad illustration (presumably for a local barber shop), portraying a middle-aged man with a confident, friendly demeanor. It was an accurate depiction. A friend, the artist Paul E. Rendel, describes Miller as highly successful in the postwar years. He was always well-dressed—never without a tie and a hat – and even purchased a new convertible every year.

- By the 1970s, Miller's professional career had begun to wane. Despite his advancing age, he kept up his network, participating in an informal roundtable of local advertising artists that would meet weekly at Stouffer's Restaurant. One of the artists, Frank Webb, convinced him to take up watercolor, which soon showcased a new dimension of talent.

- Miller also produced a series of Pittsburgh landscapes. Unlike his generally anonymous advertisement illustrations, the landscapes represented a personal marketing opportunity. Miller offered the series in prints and on greeting cards, and he even convinced Iron City Beer to feature them on a collector's set of beer cans. The artist hoped for a breakthrough success, as his personal finances were suffering as he approached retirement. But the breakthrough proved elusive, and his colorful series gradually faded from memory.

- After a successful career, toward the end of his life Miller increasingly found it difficult to make ends meet. The artist still had a personal collection of his Westinghouse posters and finally turned to them as a source of income. He approached the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History, which purchased the posters for seventy-five dollars each. Included was the not-yet-famous "We Can Do It!" It remains one of only two known original copies, making the Smithsonian's purchase an astoundingly successful art investment.

- Miller died on September 2, 1985, only four days after the Smithsonian approved the purchase of his posters. He was eighty-six.

"It is both unfortunate and extremely ironic that the artist behind one of the most recognized pieces of art in world history has remained a veritable mystery until now," said Kimble. "Perhaps now this great American graphic artist will begin to receive some of the recognition that he, like his work, deserves."

"Famous but Unknown: An Introduction to J. Howard Miller," published by the University of Chicago's Source: Notes in the History of Art.

Barbershop illustration image courtesy of a private collection.

Categories: Alumni, Arts and Culture