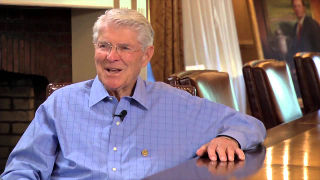

John Mooney '55: Co-Inventor of the Three-way Catalytic Converter, National Medal of Technology Winner

Sunday, October 14th, 2018

He wrote the first paper for the United Nations in 2004 to convince a few holdout countries to eliminate lead from their gasoline. The other is a new paper out of the University of Michigan asking if the 230 million or so automobiles in the United States represent a peak. (Unlikely.)

Mooney, a chemical engineer, chose the reports to illustrate how dangerous internal combustion engines can be. But something else slips from the envelope with them: His passion for tough problems — and innovative solutions.

"If you don't think there's a solution, then you just haven't asked the right question," says daughter Elizabeth Convery, 48, quoting a mantra her father often tells his five children and 14 grandchildren to live by.

That fits. John Mooney is the co-inventor of the three-way catalytic converter, a small exhaust-cleaning device that hangs beneath about 80 percent of automobiles. Each converter destroys about 98 percent of a car's three most noxious emissions — simultaneously.

"That was a phenomena that no one else thought was possible," says Mooney.

Not for lack of interest. By the late '60s, thick smog around Los Angeles sparked public demand for cleaner air, says Joseph Kubsh, executive director of the Manufacturers of Emission Controls Association (MECA). An extension of the 1963 Clean Air Act was on its way in 1970, with the Environmental Protection Agency and emissions standards in tow.

The standards would force most automakers to add a catalytic converter to their cars. A lot of companies wanted to sell it to them. That included Engelhard, Mooney's employer, a chemical company based in Iselin, N.J., now part of BASF.

But a good device wasn't so easy to build.

The chemical reactions that clean up a car's most noxious pollutants are very different. Oxygen has to be stripped away from nitrous oxide, but must also be added to carbon monoxide and unburnt hydrocarbons. Most thought this would require a bulky, two-stage system.

Mooney thought he could do it in one. He proved it by doing something unexpected.

Rather than looking at the exhaust, he focused on the gasoline being fed into the engine. If it was mixed with the right amount of air, the exhaust would offer a one-stage converter just enough oxygen to simultaneously render all three pollutants harmless.

Mooney's discovery seemed like magic.

"No one really believed me," he says. "Probably our competitors didn’t either."

But Mooney was never one to give up easily. Take his first car, a 1941 Ford convertible he bought in 1949 to carry him to Seton Hall University, where he was starting work on an undergraduate degree in chemistry. The car worked — but not well enough. So Mooney, 19, took its engine apart, leaving more than 100 pieces scattered across a friend's garage. Problem was, he didn’t know what they did.

That was no problem. Mooney talked to some mechanics, and soon knew what he had to do. The big V8 was rebuilt in time to roar north for a summer road trip to points unknown. A faint smile spreads across Mooney's face as he remembers the old car. "It had a nice noise to it," he says. "It purred."

That can-do spirit carried the day with the three-way catalytic converter too.

It inspired his boss and co-inventor at Engelhard, a scientist named Carl Keith, to send him around the world in the early '70s to convince automakers to add an oxygen sensor to their engines. The sensor would monitor the fuel-to-air ratio so each engine could be tuned to the sweet spot where Mooney's one-stage converter would work.

Volvo listened first, and by 1976, the device was rolling off some of its assembly lines. Just about every automaker would soon follow suit.

The results are legendary. BASF says the three-way catalytic converter has destroyed more than a billion tons of nitrous oxide, carbon monoxide, and hydrocarbons since it was released. More impressive: To protect the device from damage, highly poisonous lead has been removed from gasoline in nearly every country.

"It's really an amazing thing that's been created," says MECA's Kubsh.

Mooney breathes, sucking in fresh, clean air. He couldn’t agree more.

This article originally appeared in Seton Hall Magazine.