History Rediscovered: The Holy Alliance of the Catholic Church, Seton Hall University, and Iconic Labor Rights Activist Cesar Chavez

Thursday, March 21, 2019

At 2:00 p.m. on March 27, the Joseph A. Unanue Latino Institute will be hosting an exhibit and panel on the Catholic Symbolism of Cesar Chavez and the Labor Rights Movement, in collaboration with University-wide Charter Week. The event will be taking place in the Chancellor's Suite with the exhibit opening at 2:00 p.m. and the panel discussion starting at 2:45 p.m.

The event came about through the discovery of a small article within El Malcriado, the newsletter for the United Farm Workers (UFW) Union, which grew into a massive array of news stories, pursuing leads for clues, and finding the stories of a past seemingly forgotten.

The history of the United Farm Workers of America dates back to 1962 and quickly transitioned to become the first and largest union for farm workers. Predominantly, the workers were migrants, of Hispanic/Latino background, and adherents of Catholicism. The organization originated due to a merger of both the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), a majority Filipino farmworker association, and the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), the main predecessor of the UFW that was organized by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, rising union and social activist figures. The alliance came about through the shared solidarity of the Delano grape strike in California that was started by the AWOC. The vote that provided the decision for the NFWA to join the strike happened in Our Lady of Guadalupe Church (Iglesia Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe), a Catholic Church. The two organizations became one singular force for change, the UFW. What followed from the transformation of the UFW were years of protests, strikes, boycotts, and a legislative legacy that still benefits thousands.

The UFW arose out of the need for better working conditions on farms and to serve as a rebuff for inhumane work treatment that included but was not limited to: subpar wages, lack of sanitation, no workplace protections, and a whole host of malfeasance. The UFW's first fights included the boycott against Delano Grapes and lending its support to striking farmers of the rose industry, the former action morphing into one of the largest nationwide boycotts this country has ever faced.

Not long after their victory against the rose industry, the UFW in 1967 began to strike against the Giumarra Vineyards Corporation, California's most prominent grape grower. As a response to this pressure, rival grape growers actually began to allow Giumarra to utilize their own labels to sell their products. Not to be deterred, the UFW boycotted against every single grape grower in California, and as a result, adding another target during the Delano grape strike. The battle waged against the farm owners growing grapes widened to include all non-union lettuce.

The Delano grape strike did not end until 1970, with workers gaining the right to collectively bargain with the farm owners. This was a massive victory for the UFW but their fight for worker rights was not abated. The collective action against non-union lettuce and other vegetables continued well into the seventies. Their grape strike was also renewed in 1973 after vicious attacks against migrant workers transpired and union contracts were not renewed. The primary offender during this new wave of action was Gallo wines.

During the time of the UFW's activism, they grew a base of support from acclaimed politicians like Senator Robert F. Kennedy, activists such as Dorothy Day and Martin Luther King Jr., and religious support from different faith traditions. Most prominently this religious support came from the Catholic Church. From clergymen to the Pope himself, Catholic leaders and laymen openly and fiercely supported the UFW movement and praised Chavez as a man of integrity. As a devout Catholic, Chavez even ended his 25-day hunger strike in 1968 by receiving the body of Christ, sitting next to Senator Kennedy.

So integral was that support that Seton Hall University in 1974 held their inaugural Migrant Symposium, which was fully open to the public. The event's purpose was to bring together community and social leaders in their support of the UFW and migrant workers. The University invited Chavez to speak but unfortunately couldn't attend due to medical reasons. In his place, Huerta came to speak at the event which saw over 200 people in attendance. "We are happy to express solidarity with the aims of Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers," Msgr. Thomas Fahy, then president of Seton Hall, said as cited by the December 1974 edition of El Malcriado. "As well as other individuals and organizations who are trying to better conditions of farm workers in this state and throughout of country." These were few of the pieces of information revealed within the newsletter but it served as the gateway for further details to be unearthed about the relationship between Chavez and the Catholic Church.

University libraries and archives were contacted to examine additional information surrounding the event and the Catholic Church's role within the labor movement. Most notably, the Catholic University of America which houses the Msgr. George Gilmary Higgins Collection was sought after. Msgr. Higgins was a significant leader within the Church and a staunch activist for social justice, regarded popularly as the "labor priest." Requesting access to certain boxes within the collection yielded correspondences between himself, Chavez, Msgr. Fahy, and Cardinal Peter L. Gerety, the Archbishop of Newark from 1974-86. In those correspondences, Msgr. Higgins conversed with Chavez, commending him for his outstanding work and lauding praise for Chavez's devotion to the Gospel and its ecclesial message of nonviolence. Many of Chavez's messages to Msgr. Higgins and others ended with the popular religious parting, "Your brother in Christ."

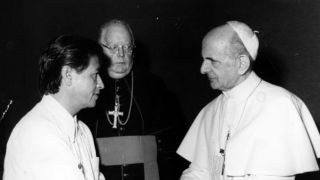

What was further unveiled from those documents included the UFW sending their draft constitution to the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in order to gain the Bishops' approval before the Constitution was finalized. Very importantly though, details of a private audience between Chavez and Pope Paul VI in 1974 were discovered. During this meeting, Chavez was welcomed as a "representative of the Mexican-American community" and a faithful son of the Catholic Church. Pope Paul VI offered his support to UFW's political activism in support of the American migrant farm workers. This meeting that took place within the Vatican itself happened mere months before the Migrant Symposium at Seton Hall.

After reviewing the Higgins collection, additional resources were compiled from the Seton Hall Walsh Library pertaining to the Migrant Symposium. While examining the microfilm archives of the Star-Ledger, articles were found from 1974 detailing the planned event. Other articles detailed legislatively what was occurring within NJ to protect farmworkers. Interestingly, articles from The Star-Ledger and another article from the November 1974 edition of El Malcriado described how NJ State Assemblyman Byron Baer was drafting legislation to safeguard migrant farmworkers with his bill, A1039. The bill intended to place the responsibility of worker safety with the farm owners, effectively ensuring that the farm owners could not neglect the health and well-being of their workers. "We fully support this bill," Msgr. Fahy said during the seminar as reported by El Malcriado. "And urge bringing it to a vote promptly. This would be the first step toward gaining basic humane treatment for a group of people long neglected in our society."

Assemblyman Baer was one of the many attendees at the symposium and spoke of the significance of the event. He said, "Nothing like this symposium has been tried before in the state." He described how the symposium would prove to be valuable for the migrant worker movement within New Jersey.

Subsequently, the Archdiocese of Newark was contacted to further gather more details about the symposium. What was uncovered there not only included original articles surrounding the event from the Catholic Advocate, the Archdiocese's newsletter, but other events sponsored by the UFW and the Catholic Church in New Jersey, working hand in hand for one struggle; migrant-worker justice.

Seton Hall's prominent support of the UFW was not limited to the symposium of 1974 but was present before and well after the event occurred. In April of 1974, there was a rally conducted on campus in support of the UFW with over 100 people in attendance. "The Church must be a voice for the voiceless," Auxiliary Bishop John J. Dougherty announced to the crowd. Msgr. Fahy was also present at the event and welcomed the demonstration of Catholic social teaching, which illustrates the Church's position on human dignity and the good of society. A little over a year later, the Advocate reported that thousands of people planned to march 15 miles to Seton Hall in support of farm workers. This walk-a-thon served as the main event in honor of Farm Workers Week and was co-sponsored by the National Farm Worker Ministry and the UFW. There were multiple starting points for this march, most originating from Catholic parishes and locations.

Other Advocate articles documented the Catholic Church's support throughout the country. In August of 1973, a total of seventy-six priests, nuns, and seminarians were released from Fresno County jails after striking in solidarity with UFW workers. They spent two weeks in jail and argued that the UFW workers arrested with them should have been released, too. This and supplementary documents show that not only did the support of the Catholic Church come from those in powerful positions but consisted of clergymen and laypeople as well.

All the information and sources collected constructed a timeline for how Chavez and the Catholic Church alliance became intertwined with one another. From correspondences between Msgr. Higgins, Cardinal Gerety, Chavez, and Huerta, which led to Chavez's private audience with Pope VI and his vocal, exceptional support of Chavez and the UFW movement, to the planned Migrant Symposium and rallies in NJ, the evidence is clear - the labor rights movement was becoming a tangible symbol of the Catholic Church. The Catholic Church was adamant about supporting migrant labor rights and Chavez consulted with those within the Church hierarchy regularly for guidance. Much of this information is not known currently to the Seton Hall campus community. This lack of awareness about the campus' own role within the labor rights movement provided the inspiration for the Unanue Institute in organizing an exhibit and panel dedicated to illuminating the past.

The exhibit will show all the copies of newsletters, newspaper articles, photographs, and correspondences retrieved from various sources of this project. Original copies generously donated from the Archdiocese of Newark archives will also be displayed for public viewing.

Following the exhibit will be a panel discussion on the Catholic Church's role on the labor movement and social activism as taught within Catholic social teaching. The featured speakers include Assistant Professor Anthony Nicotera of the Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Social Work, and Father Jack Martin, who spent more than 50 years of his life as a dedicated civil rights activist advocating for the betterment of those marginalized within society. Attendees will be intrigued to learn that Father Jack met with the UFW leader during Chavez' visit to St. Ann's Parish in Newark, NJ on July 1, 1974.

The Unanue Institute gratefully thanks the work of journalists, photographers, librarians, and archivists whose dedication to their crafts made this endeavor possible. The Unanue Institute also thanks the advocacy work of the UFW, Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, Assemblyman Baer, Msgr. Higgins, Msgr. Fahy, and their allies within the Catholic Church, for championing human rights and remaining steadfast in their unwavering support against worker exploitation.

Si, se puede! Viva la Causa! Viva la Huelga!

For information on future events, scholarships, and all that is #JAULI, stop by the Institute's office located in Fahy Room 246. Don't forget to follow the Institute Twitter and Instagram @JAULISHU to stay up to date with their latest news and events.