Core II Students Are Reading New Testament and Plato

Friday, January 17, 2020

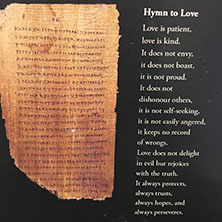

Hymn to Love written in English and also in the original Greek, on a very old papyrus (c. AD 200-250), found in Egypt but now housed in the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin.

Welcome to the Core, particularly to Core II, which is being taken by a very large number of students this semester. This course deals with "Christianity and Culture in Dialogue," so a key component of the course involves looking at ideas, both Christian and non-Christian, and how they interact with each other. It can be imagined almost like a conversation (i.e. dialogue) though the texts may have been written centuries apart. During this first week, focused on the ancient world of both the early Christians and their pagan predecessors and contemporaries, students read either of two letters from the New Testament (Paul's First Letter to the Corinthians or John's First Letter), as well as a text from the non-Christian world of the Greeks, Plato's Crito.

Plato's text, from the fifth century before the time of Christ, focuses on the dialogue between Socrates and his student, Crito, in which the former reasonably convinces the latter that it is right for him to submit to the decree of an unjust state, which has sentenced him to death. Socrates is not saying he thinks the state is right to order his execution. On the contrary, his refusal to submit to the demand from the state's officials that he stop teaching and "corrupting the youth," as they argued, is what led to his being condemned. However, as Plato recounts the conversation, Socrates argues that, even when the state is unjust, though it must be challenged (as he has done), it still must be obeyed if one can do it in a good conscience. For him, that meant that he must submit to an unjust death sentence, as his trying to escape, he argues, would be immoral and would give a bad example of cowardice and selfishness to his former students and the whole younger generation. The key to Socrates' argument is that principle must preside over ease, virtue over safety. In the end of the dialogue, Crito is convinced of the painful reality that Socrates must die.

The two Christian texts also focus on virtue and the choice of principle over ease as well and certainly over wickedness. However, they both go beyond virtue to the love that underlies it and even inspires it. Though one could argue that Socrates also is motivated by love (of his students and certainly of the truth), the primary argument of his reasoning is that not escaping his death sentence is what is logical and rational. In First John, the key idea is love, which in any Christian text will always be linked, with truth. He says, "I write to you, not because you do not know the truth, but because you do know it, and you know that no lie comes from the truth" (1 Jn. 2:21) However, underlying the truth is the "message you have heard from the beginning, that we should love one another" (1 Jn. 3:11). One of the biggest lies would be to claim to love God and not love our brothers and sisters: "Those who say 'I love God,' and hate their brothers or sisters, are liars; for those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen" (1 Jn. 4:20). This love must be practical and giving: "How does God's love abide in anyone who has the world's goods and sees a brother or sister in need and yet refuses help?" (1 Jn. 3:17). It is also pure: "The love of the Father is not in those who love the world; for all that is in the world – the desire of the flesh, the desire of the eyes, the pride in riches – comes not from the Father from the world" (1 Jn. 2: 15-16). And, in one of the most beautiful passages in Scripture, it frees us from all fear: "There is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear" (1 Jn. 4:18).

This kind of love is also described in Paul's first letter to the Corinthians in the famous chapter 13. Recently, a friend gave me a postcard with this beautiful Hymn to Love written in English and also in the original Greek, on a very old papyrus (c. AD 200-250), found in Egypt but now housed in the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin. Seeing the passage on the ancient scroll and the contemporary translation is very moving, and the love described, the Greek agape, is the same as that love described in First John. "Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast…. It is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered." Paul goes on to talk about what love does: "It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, and always perseveres." The Greek word for love here, agape, was not typically used in the first century. It was the early Christians who popularized it, and its Roman translation – caritas – came to us in English as "charity." But it means much more than simply giving of one's surplus to others. As Paul says, if we give up all our possessions "but have not love" it "profits us nothing." The love described in First John and First Corinthians 13 is living, active, self-sacrificing, and powerful.

As we begin a new semester, let's take these ancient texts with eternal meaning to heart. As we discussed in my Core II, we should consider what made Socrates feel the truth was worth dying for? What does John's letter suggest about how truth should inspire us to live? And as we look at Paul's Hymn to Love, how does it apply to those in need, to people on the streets, to refugees in detention, to people lost in addiction and other kinds of suffering? These are the questions we can begin to answer as we explore the texts in Core II.

Categories: Campus Life, Faith and Service